1

HOME > Business >

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO CONSUME LUXURY TODAY?

Written by Julian Randall in Business on the 18th April 2023

The concept of luxury has become one of the most contentious topics in fashion today. Consumers and industry practitioners continue to grapple with the defining elements of the term, generating a great deal of ambiguity around what constitutes a luxury product. These tensions are potent within the world of fashion for many reasons; production levels, consumption motives, and the conspicuous nature of dress, to name a few. And I partially attribute this uncertainty to scholars’ reluctance to land on a consensual definition of luxury. I suppose it’s only natural that if those whose job is to do the heavy intellectual lifting are hesitant to define it concretely, this will produce some ambivalence in popular discourse. But the vastness of how we consume and experience “the finer things” is one of luxury’s core attributes: multidimensionality.

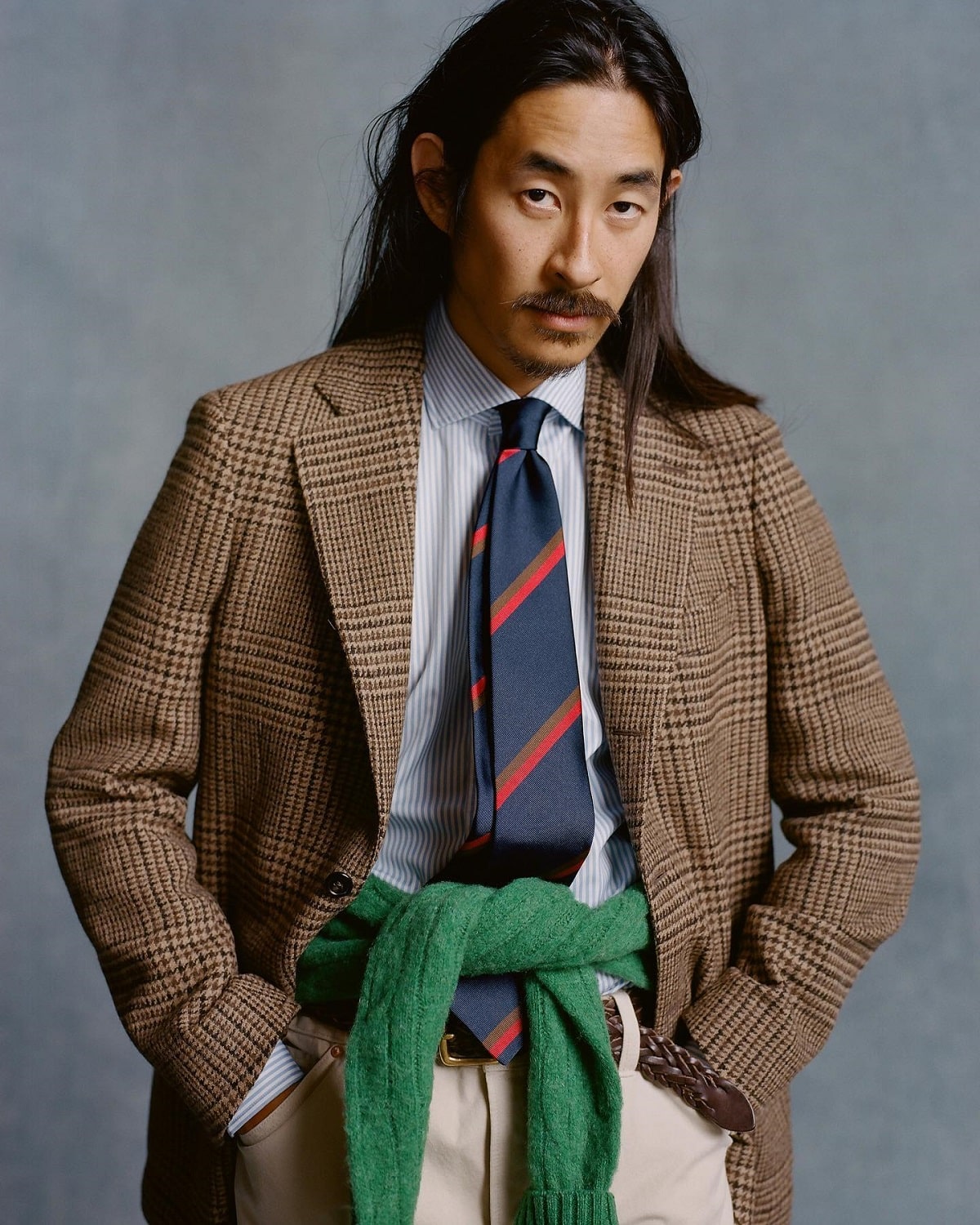

Perhaps the vintage blazer your grandma passed down to you, made by an unknown tailor, is luxurious on the basis of your personal relationship with it as its construction. This is part of the democratisation of luxury that doesn’t get the explicit attention it should. I think approaching luxury as a wide-ranging construct could allow multiple entry points for engaging with the topic and hopefully lessen our anxieties around it.

What is luxury, anyway? Most of us conceive of it in a linear, traditional sense consistent with the old guard; the finest and rarest textiles, the exclusivity of a product, or an “elevated” aesthetic standard. While those qualities certainly don’t elude luxury, they are not confined to them. Gucci and Louis Vuitton have been particularly vulnerable to criticism due to their popularity and production of canvas goods. Because despite luxury’s democratisation over the last several years, consumers detest it--hence the recent attention to “quiet luxury” and “stealth wealth”. And in the pursuit of maintaining one’s status within the consumption hierarchy is also an urge to relegate another’s (guilty!). I’ll admit to turning my nose up at a store customer shopping a brand they seem to possess no history of or genuine connection to. We’ve all done it at some point.

But consumer snobbery truly rears its ugly head when it comes to logomania, often seen as tastelessly showy. Or one of my favourites; the annual Twitter debate on whether a purchase from staple American fashion brands Coach and Michael Kors is considered luxurious. The subjective nature of the topic is what excites me as a fashion thinker. My issue, however, is that each view attempts to place luxury in a box it just doesn’t exist in. It’s more fluid than we’d like to think. Luxury is what (Wiedmann et al., 2009) describe as “a subjective and multidimensional construct” that “should follow an integrative understanding.” These dimensions are the financial, functional, individual, and social values of the luxury construct.

You can read the article here, but the current discourse on luxury fashion presents an overreliance on the financial and social aspects. Unsurprisingly, both dimensions overlap with status consumption, which luxury consumer behaviour is often reduced to. For example, the visibility of a product price on a brand’s website might give one consumer a perception of another consumer’s class. Wearing a t-shirt from a luxury brand could indeed support such perceptions. This form of consumerism is still present, but other types of consumer culture, as evidenced and led by Hip-Hop artists, allow for a more expansive discourse on luxury. Today, you might find Atlanta rapper Gunna carrying a suede Chanel flap bag or Kevin Gates with a Louis Vuitton scarf on his braided ponytail. What about A$AP Rocky and Pharrell sporting womenswear? This shift towards a more delicate appearance recently trickled down to young men adorning themselves in pearl necklaces and Hermes scarves. How might this reflect uniqueness and identity? Exploring the concept of luxury in this way helps us to interpret consumer relationships with luxury in a much richer way.

Also, how we categorise luxury brands has as much of a bearing on these discussions as our consumption of them does. Pharrell Williams’ appointment as Men’s Creative Director for Louis Vuitton revealed this. Some despised it; others were ecstatic. For me, the more interesting conversation was around the perceived deemphasising of craftsmanship and quality in luxury fashion overall. Many headlines perpetuated these narrow qualifiers that shape our ideas of luxury when in reality, many brands prioritise artisanship whether or not they have the backing of a conglomerate. I mean, Cleveland-based William McNicol of William Frederick Clothing is making such timeless, sophisticated menswear in the Midwestern U.S. Quilting and knitwear is one of the most intimate artistic practices a maker can undertake (hello, individual dimension!). As paradoxical as this may sound, broadening the scope of what we consider a luxury brand could encourage a flattened, less vexed culture of luxury consumption.

Revisiting the critiques of Vuitton and Gucci due to their uses of PVC-coated canvas: this calls for a consideration of utility, one of the functional dimensions of luxury value. Canvas is a versatile, reliable fabric that will outperform leather in everyday use. Similar assessments have been made of other luxury brands’ uses of nylon. In short, anything that isn’t leather, cashmere, or wool is viewed as less luxurious, which is devoid of nuance. Brands often have fabrics made exclusively for them, even if they are used to produce products that happen to be the cheapest ones for consumers to buy. And if a shopper’s desire to purchase something from a brand is inspired by their favourite celebrity or a subcultural style, or it simply does the job, that could be enough. The variance of luxury itself says so. I’m not as interested in policing people’s consumption as I am invested in promoting intentional shopping, high fashion included. As encouraged by the aforementioned scholars, a multidimensional approach can serve as a starting point for that, in addition to considering what it means to consume luxury today. The way I see it, as long as you develop a language for your luxury affinity within the proposed construct (or one of your own), have at it.

Julian Randall

Julian is a fashion writer with a luxury retail and marketing background. His Ph.D. research currently focuses on men's consumption of luxury fashion in America. So naturally, he encourages a more considered approach to style and shopping. Other interests of his include Hip-Hop, loafers, and all things black truffle.

Trending

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10