1

HOME > Business >

WHAT THE FUTURE MAY HOLD FOR J.CREW

Written by Ivan Yaskey in Business on the 15th July 2021

It’s an understatement to call the trajectory of J.Crew a rollercoaster. What caught wind as an alternative to high-dollar prep fashions eventually evolved into officewear basics before, in an Icarus-like move, stretching toward Fashion Week aspiration, only to be undermined by poor-quality construction and designs that no longer resonated with their core consumer. Through multiple CEOs and creative directors, J.Crew has shed various identities, with the latest, at least for menswear, being prep-centric streetwear. Spearheading what’s essentially yet another retooling packaged as a rebranding effort is Brendon Babenzien, who got Noah off the ground with a similar aesthetic back in 2015 and contributed significantly to Supreme’s ascent as a formidable and veritable fashion brand. Yet, J.Crew’s rebranding isn’t simply introducing new silhouettes to a consumer tired of business-casual basics: It’s attempting to find a new identity – and subsequently a consumer to go with it – in an American culture currently thumbing its nose at the faux-aspirational white upper-class lifestyle of sailing off Martha’s Vineyard and weekends at gated country clubs.

Let the Rebranding Begin

Back in May, the J.Crew Group put out a press release announcing Babenzien’s appointment as the new Creative Director of its men’s division, with the goal of “refining” the brand – specifically, infusing its classic designs and image with a stronger, more independent direction and subculture attitude. Babenzien, in this case, isn’t a newcomer. As Design Director, he transformed Supreme’s offerings and scope from cult skate brand into something resonating across a broader marketplace. In founding Noah, Babenzien essentially merged what could be described as J.Crew prep basics with more of a streetwear-rooted vision – not taking itself too seriously, not class-exclusive, and still inspired by skate culture. Noah, essentially, became Supreme for the more discerning, grown-up consumer who’s not interested in building his wardrobe at Express or Brooks Brothers. In fact, Babenzien admitted in the press release that he’s built part of his personal style from J.Crew, showing he’s more than just a hot commodity invited to turn a failing brand around. “I'm excited to join the team and build a positive future that meets the interests of the thoughtful consumers that exist today,” he stated, “Satisfying not just their sophisticated taste level but their demands for responsible business practices." J.Crew, now under the direction of CEO Libby Wadle, sought out Babenzien to deliberately shake up their brand, step out of their comfort zone, and progressively adapt their business model – for instance, manufacturing garments more sustainably.

Where J.Crew Went Wrong

J.Crew’s steep decline started about a decade ago, off its high of endorsement from former First Lady Michelle Obama and influencer-like women’s creative director Jenna Lyons. As of May 2021, the company operates 151 J.Crew stores – although none in the UK – and 143 for Madewell, its more successful casual, denim-centric partner brand that expanded to menswear just a couple of years ago. These are joined by J.Crew Factory outlet stores and a corresponding website. Just a few months into the pandemic, the company filed for bankruptcy while, at the same time, shifting its strategy to turn Madewell into its flagship brand. At J.Crew’s height, it had over 500 stores in 100 countries and was spotted on the red carpet, on leading American politicians, and in offices across the world. But, sales took a strong hit just a year later, decreasing $607.8 million year over year. J.Crew’s history goes back to 1947, when it was launched as a door-to-door sales endeavour by Mitchell Cinader and Saul Charles as Popular Merchandise. Menswear wasn’t part of the portfolio: Instead, the brand found its niche among price-conscious female consumers. Its first rebranding occurred in 1983 with the arrival of the J.Crew catalogue. Imagery and garments reflected what you’d see from Ralph Lauren and Brooks Brothers at a lower price point. Brick-and-mortar stores followed at the end of the ‘80s and growth over the next decade was relatively steady. Eventually, by 1997, TPG Capital bought a share of J.Crew and, in the process, appointed Millard "Mickey" Drexler as CEO just a few years later. Drexler collaborated with Lyons, overseeing its women’s division at that point, to play up the brand’s heritage appeal. The company went public in 2006.

Around this era, Madewell – starting with womenswear – made an appearance to target a younger demographic wanting high-quality everyday basics. Even through the Great Recession, J.Crew persisted, seeing year-over-year gains as its competitors took a major hit. As the U.S. recovered economically, TPG Capital bought out J.Crew officially. What followed remains as J.Crew’s glory years, unless we see some kind of turnaround: Paparazzi photographed A-listers like Reese Witherspoon and Gwyneth Paltrow in its staples, while Michelle Obama was frequently seen in the brand during her husband’s first term. Yet, while J.Crew simultaneously symbolised upper-class business casual – and even proper business dress, if you were wearing one of their Ludlow suits – it eyed true Fashion Week status. As such, we started spotting more colour variation over these years – and, among women’s offerings, the occasional smattering of sequins or sheer material. The aim was hit and miss, with more misses. Customers complained the clothing no longer suited office wardrobes and noticed that prices steeply increased while quality declined. Reports likened it during these years to a fast-fashion brand. As a result, J.Crew stopped delivering for TPG Capital and, in a slow slope into 2020, began a gradual decline as Madewell picked up business. Drexler and Lyons both left around this time, only for a revolving door of CEOs and creative directors to come and go. While prices eventually lowered and plus-sizes were finally added, J.Crew shifted its strategy too much in the other direction, focusing primarily on its discount offerings while ignoring the construction and variety of its flagship brand. By May 2020, steadily decreasing sales accelerated with the Covid-19 pandemic, and J.Crew announced its plans to file for bankruptcy and reinvent itself in response to a $78.8 million net loss and $1 billion of debt. As this occurred, they intended to file an IPO for Madewell, although this move was postponed, to help grow the portfolio of brands in a new direction. Babenzien’s appointment serves as an itineration of this approach, essentially called upon to overturn what hasn’t worked in a number of years.

Why Invest in Streetwear?

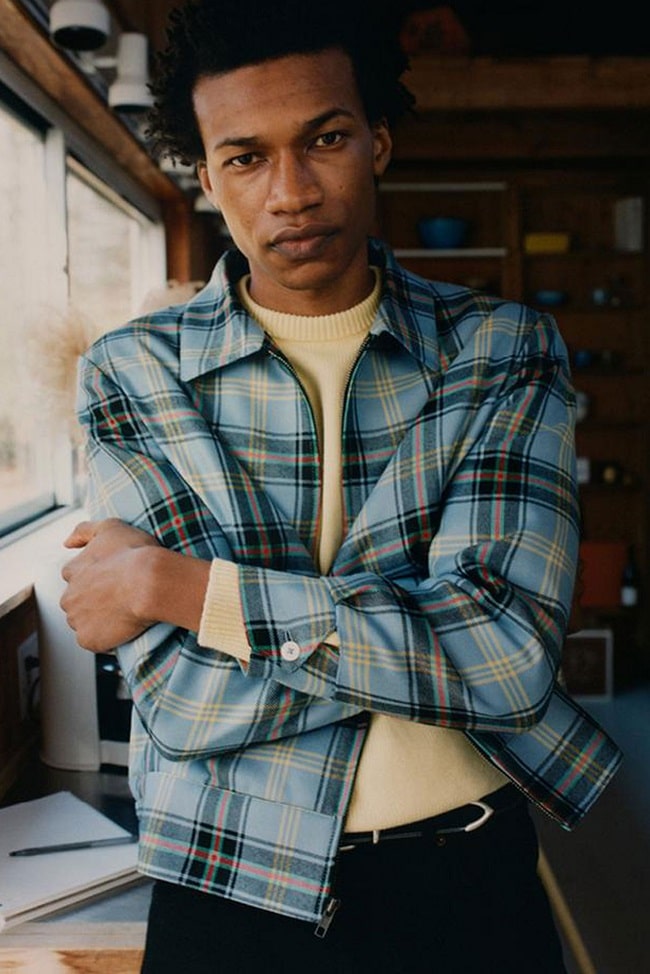

For most of J.Crew’s history, preppy fashion and streetwear didn’t run in the same circles. Now, though, social expectations and what’s considered aspirational are experiencing a degree of overhaul. The Ralph Lauren lifestyle J.Crew once provided an alternative to looks simultaneously classist and racist and intentionally exclusionary. Instead, building off Babenzien’s resume, Supreme drops have replaced pastel polos, argyle sweaters, and boat shoes as a status symbol, no matter where you fall within the class hierarchy. As such, going forward – for any brand in 2021, not strictly J.Crew – involves examining your history and the message you’re sending. Aligning with – or at least taking inspiration from – streetwear is a first step toward seeming more approachable and aspirational in the present. At the same time, streetwear not only overlaps with and greatly influences runway-level fashion, but has started appropriating and reworking questionable elements for a more discerning, youthful consumer. A couple of years ago, “dad” fashion and gorpcore exemplified this, translating tapered, semi-shapeless silhouettes into something desirable. The result, now less novelty, is ubiquitous: pockets on everything, high-waisted trousers, and less-dowdy pleats. Noah, Babenzien’s brainchild, did this in a more subdued fashion, with a rippling result. “Prep,” today, means taking the styles we in the present associate with a sneering ‘80s teen villain – think James Spader in Pretty in Pink – and adding more saturated, if not neon, hues and oversized fits. The so-called outcasts have taken the garments of those deeming themselves at the top of the social hierarchy and reworked them on their terms.

This prep-meets-street approach seems to be the hope of J.Crew. While that’s not entirely auspicious – as already mentioned, this is what Noah has done successfully since day one – the question then becomes, “How will this move resonate with J.Crew’s core consumer?” J.Crew’s waning reputation, due to decreased quality, may end up being its death knell among office workers who built wardrobes of its comfortable basics for a couple of decades, unless Babenzien’s appointment results in hypebeasts legitimately considering J.Crew – or if its old-school preppy reputation will overshadow any developments forward. The image switch isn’t that much of a stretch – much of Noah looks like oversized J.Crew meets Stussy – but more of a case of if anyone’s paying attention to notice. Still, hybrid streetwear collections resonate with consumers wanting more than a box tee. Supreme has aced the button-down and blazers game with Comme Des Garcons, Fear of God seamlessly transitioned to suiting while collaborating with Ermenegildo Zegna last year, and outerwear brands like Moncler, Canada Goose, The North Face, and Columbia seem to understand when more colour and patterns are needed.

Not a New Move

J.Crew is essentially borrowing a strategy long-time, if not languishing, brands have attempted over the past decade to reinvigorate their image and connect with a new, often youthful consumer. Although the creative director doesn’t have to come from a streetwear background – case in point, Alessandro Michele at Gucci – it definitely helps. Right now, we tend to associate this progression with the appointment of Virgil Abloh at Louis Vuitton, and how he’s since translated Off-White’s in-demand minimalism and classic streetwear silhouettes to suiting. In more modern memory, Raf Simons ignited this transition: Although critics will debate whether his eponymous line is truly streetwear, his designs have held their influence on streetwear-centric brands. Simons’ own background partially reflects the DIY streetwear story: He began as a furniture designer and, teaching himself apparel construction, launched his own brand in the mid-‘90s. His vision then enhanced designs for Jil Sander, Christian Dior, Calvin Klein, and, as of 2020, Prada. While only at Calvin Klein for roughly a year, his appointment temporarily resulted in a surge in sales and gave us the edgier ready-to-wear 205W39NYC. Yet, the sudden image change for Calvin Klein never truly resonated with audiences, and Simons ended his contract after less than two years. If Simons’ vision for Calvin Klein seemed too experimental, other appointments have seemed more fruitful: Demna Gvasalia switching from Vetements to Balenciaga, Matthew Williams at Givenchy, and Fear of God’s Jerry Lorenzo for Adidas’ basketball division. Retaining the brand’s core essence while viewing it through a hyped designer’s specific lens seems to be the magic formula, so we’ll have to see how this plays out for J.Crew.

Trending

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10