1

HOME > Trends >

IS THERE ANY MORE INNOVATION LEFT IN STREETWEAR?

Written by Ivan Yaskey in Trends on the 29th January 2020

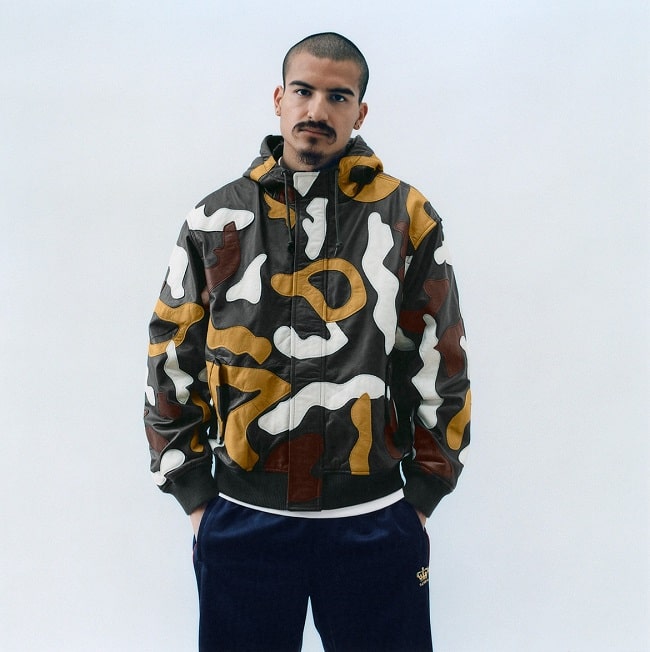

The same silhouette. The same group of designers scheduling drops. Even for the up-and-comers, a particular formula is at play: Wide-legged trousers, slouchy sweatshirt, and a snapback, perhaps with some graphics mixed in. Contrary to the streetwear we thought we knew (or the styles from 20-plus years ago we nostalgically pine for), everything today seems assembled by an algorithm.

The result is rather boring and ordinary, and appears to fly in the face of yesteryear’s subversive, counterculture attitudes and anti-fashion stance. In a sense, streetwear has evolved into the thing collective scenes likely feared most: An overly trendy, us-or-them movement that’s devoid of individuality, character, and brashness. All in all, it’s so chill, it’s practically soporific.

You’d have to say that it’s been since 2014’s Health Goth Movement (remember that?) that we saw a different streetwear silhouette that has managed to be interesting yet practical. Virgil Abloh and Demna Gvasalia, in their respective, elevated efforts for Louis Vuitton and Balenciaga, get close, but they appear to be a collage of familiar concepts or simply take those concepts and greatly exaggerate them to the point of parody. In another sense, streetwear’s like any EDM subgenre characterised by a specific group of sounds, but the production aspects are so targeted, there’s nowhere else to go. Thus, the subgenre disappears down into underground Soundcloud obscurity (hello, Eurodance and Melbourne Bounce), and its producers evolve their sound into something completely unrecognisable. Thus, it’s likely time for the streetwear scene (or, more appropriately, the Instagram version of it) to let go of the familiar tropes and shakily move onto something new. But, where else could it go?

Back to its Roots

Streetwear used to be local or defined by a particular scene or subculture. You still see the remnants today – the vague allusions to hip-hop or skate culture, perhaps punctuated with notes of punk, grunge, or dance in varying degrees. Yet, much of it has blended and fused into a bland amalgamation that’s not one particular thing or another. Yes, cities that haven’t quite been transformed all the way with the mega-gentrifying boom that’s hit everything like a bull in a china shop over the past decade still maintain some degree of character, and yes, it bubbles below the surface of the social media-fueled mainstream, but there’s no true in between. It’s either all Supreme and its hypebeasty ilk, or the upstart, perhaps strictly locally fueled or existing solely through a single online storefront. Variation, a sense of origin, and a hint of opposition are needed, rather than an urban-ish, hip-hop-ish look that only finance, and tech bros can afford.

Toward a Sense of Responsibility

Within the fashion spectrum, streetwear’s the elephant in the room. Compared to the fast-fashion brands, the selective drops, in which only a limited number of products are made, appear relatively small scale. But, while drops earlier this decade seemed very gimmicky and exclusive, it’s kind of the way things are done now. And, they’re not a here-or-there phenomenon; instead, they occur, across multiple brands, with surprising frequency. At that rate, you just might as well release a full collection and be done with it.

Overlapping with this pattern, drops’ exclusive shine loses its effectiveness over time. On one hand, having no need to wear those limited-edition kicks or tee has exploded into a massive (and expected to grow) resale market. On the other, it adds to the ever-growing amount of petroleum-based substances in landfills that take years to break down. And, that’s not factoring in the environmentally damaging production and strained resources needed to create it in the first place.

Streetwear, though, has been forgiven, to some degree, or overlooked due to its below-the-mainstream nature. However, Supreme, plus mall-streetwear brands like Obey, haven’t really been underground for a number of years now, so the excuse that streetwear’s mostly an independent, small-scale operation done by guys with no formal fashion training no longer holds up.

Take the High Road

Although sales paint a different picture, few can argue that streetwear has stylistically and creatively hit a brick wall. There’s only so much a unique collab can do, aside from toss around some new colours and graphics or play up the hype factor to the right consumers. There comes a point, as mentioned above, when the same path gets tread so often there’s nowhere to go but down, and Stüssy’s trajectory, to some extent, illustrates those highs and lows and the trap subculture-influenced brands find themselves in.

Stüssy, as most know by now, built its brand on creator Shawn Stüssy’s signature-based logo graphic that first graced surfboards before it moved to clothing. Skate and hip-hop culture fleshed it out into the ‘90s, and a pre-Vice i-D magazine highlighted its fashionably anti-fashion appeal. Yet, sales declined throughout the decade, and by the late ‘90s, an overhaul was in order. As Stüssy himself became less involved, the brand sought out a new designer – settling on Valentino’s Nick Bower at the time – and adjusted its market focus from the U.S. to Japan and Europe. Design wise, the signature logo graphics remained, but Comme Des Garcons-inspired silhouettes broke things up. As such, these days, a swing by Stüssy’s site reveals more wearable pieces and a handful of ‘90s-esque logo apparel.

Although most could argue that Supreme has also made this move to some extent, with more blazers, button-fronts, and even a few Comme Des Garcons collabs under its belt, this embracing-new-terrain attitude shouldn’t just be for the top players out there, and further illustrates the notion that no one can coast on logo graphics forever. Even if the result isn’t Fashion Week-esque style, it represents a new, more evolved step that helps solidify a brand’s long-term appeal and adaptability.

Trending

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10